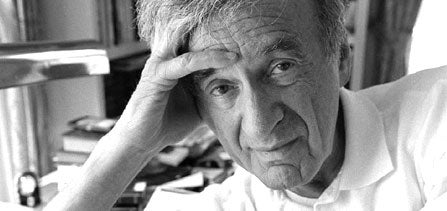

Nobel laureate and survivor of Auschwitz, Wiesel has used his incomparable talents as an educator and writer in defense of peace and human rights.

Nobel Peace Prize winner Elie Wiesel was an excellent choice to inaugurate the Wallenberg Medal and Lecture in Hill Auditorium on September 25, 1990. Widely regarded as the conscience of our civilization, Wiesel is an eloquent writer, teacher, storyteller and witness to the Holocaust. He was also among the first to promote public recognition of Righteous Gentiles—those individuals who risked their lives to save Jews.

Wiesel expressed tremendous gratitude to Raoul Wallenberg for being among the few who took the side of the victims. Wiesel called Wallenberg and his fellow Righteous Gentiles a unique species: if more people had dared to defy the oppressors, Wiesel believes, more Jewish lives might have been saved. “Why was such a good man punished?” Wiesel asked in his lecture. “And why the silence about Wallenberg for so many years?” After the war, Wiesel said, very few people mentioned Wallenberg with the exception of those Jews in Budapest he saved. “The reason is that most people were embarrassed to remember Wallenberg,” said Wiesel. “Wallenberg taught us a lesson. He demonstrated that it was possible to resist evil, it was possible to save Jews.”

Wiesel was born in Sighet, a small village in what is now Romania. In 1944 he and his entire family were deported to Auschwitz, where his mother and his youngest sister died. Soon after, in January 1945, Wiesel and his father were transferred to Buchenwald, where his father died. When Buchenwald was liberated in April 1945, Wiesel was a sixteen-year-old orphan. In his 1995 memoir, All Rivers Run to the Sea, he says of that time, “First I had to learn, or relearn, to live.”

Ultimately, he was able to triumph over the death and degradation that had enveloped his life, acting on his convictions, while maintaining his faith in God and his belief in the goodness of humanity. “It would have been so easy for us to slide into melancholy and resignation,” wrote Wiesel in his 1999 memoir, And the Sea Is Never Full. “We made a different choice, we chose to become spokesmen for man’s quest for generosity and his need and capacity to turn his or her suffering into something productive, something creative.”

Wiesel told his Ann Arbor audience that Raoul Wallenberg’s actions in Budapest had a lesson for humanity: “All of us are responsible for one another, and it is possible to be human even in an inhuman world.” Surviving Auschwitz and Buchenwald instilled in Wiesel a strong sense of duty—to bear witness for those who did not survive. “If you were there—if you breathed the air and heard the silence of the dead—you must continue to bear witness …to prevent the dead from dying again,” he said. “For a witness to remain silent is to allow falsehood to win over truth.”

Over time, insisting that it is his right and duty to interfere in crimes against humanity, Wiesel has stepped up his mission. He has worked ceaselessly for peace and human rights around the world, championing the struggles of refuseniks in the former Soviet Union; blacks in apartheid South Africa; the persecuted of Cambodia, Bosnia and Kosovo; and many, many others.

Shortly after receiving his Nobel Prize, Wiesel established the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, a forum for discussion of the dominant moral issues of our time. “We are equally responsible for each other, and I more so—if I am indifferent to others’ suffering, I am an accomplice,” said Wiesel in his Wallenberg Lecture. Wiesel’s life exemplifies the capacity for hope that is embedded in the Jewish heritage. He continues today to spread his vision of human dignity and hope throughout the world.