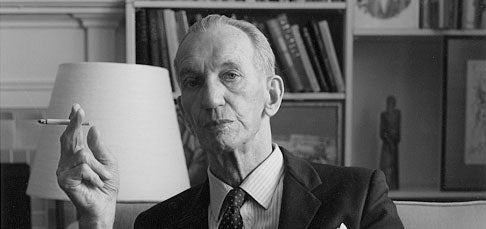

“The common humanity of people, not the power of governments, is the only real protector of human rights.”

-Jan Karski

Jan Karski was a Polish military officer and courier for the Polish underground during World War II who was an early witness to the Holocaust. Karski’s experiences as a spy for the Polish government-in-exile and for the resistance movement in Poland led to him warning the West of the genocide in Europe.

In 1939, when Germany and the Soviet Union invaded Poland at the start of World War II, Karski was taken prisoner by the Red Army and sent to a Russian camp. He escaped and returned to German-occupied Poland where he joined the anti-Nazi resistance. Brilliant and well-educated, a devout Catholic, Karski spoke many languages and had a photographic memory. He served as a courier between the Polish government-in-exile in London and the resistance organization in Poland, making numerous secret and dangerous trips between France, Great Britain and Poland.

In 1942 two leaders of the Polish Jewish underground visited Karski to inform him that more than half of the 500,000 Jews jammed into the Warsaw ghetto had been deported to death camps, where an estimated 1.8 million had already been killed. They sought his help in getting the news of these crimes to Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt, Karski infiltrated both the Warsaw ghetto and, posing as a camp guard, a transit point for Jews being sent to concentration camps. Karski was given a hollow door key that contained microfilm documentation of the extermination campaign in German-occupied Poland. He crossed occupied Europe on local trains through dangerous territory and made his way to London.

Karski relayed the first eyewitness account of the Holocaust to the incredulous and dismissive Allied leaders. He gave a detailed account to British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden who, he later wrote, “said that Great Britain had already done enough by accepting 100,000 refugees.” He crossed the Atlantic and arrived in the United States in mid-1943 to warn President Roosevelt and other government officials who refused to believe his account of the horror unfolding in Europe. Only after six more months did the U.S. act by creating the War Refugee Board to develop plans for rescuing victims of Axis oppression. A representative of this organization in Stockholm recruited Raoul Wallenberg to protect the Jews of Budapest. Karski drew from his experience a profound lesson: “I learned that people in power are more than able to disregard their individual conscience if they come to the conclusion that it stands in the way of what they see as their official duty.”

When the war ended Allied leaders expressed shock and surprise at the discovery of the Nazi death camps. Karski’s disillusionment was profound. He stayed silent about his reception until 1981, when Elie Wiesel prevailed on him to speak publicly about his experience, and he participated in Claude Lanzmann’s documentary film, Shoah. His account of his wartime experiences, My Report to the World: Story of a Secret State, was re-published in 2013.

After the war Karski emigrated to the U.S. where he became an American citizen and earned a doctorate from Georgetown University, where he had a long and distinguished career as a professor of international affairs. In 1982, he was honored as one of the Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, Israel’s memorial to Jewish victims of the Holocaust, and in 1994 he was made an honorary citizen of Israel. He received Poland’s highest civil and military decorations for his courageous actions. A biography was published in 1994 by E. Thomas Wood and Stanislaw Jankowski, Karski: How One Man Tried to Stop the Holocaust (London: John Wiley & Sons).

Jan Karski died in Washington, DC in 2000.