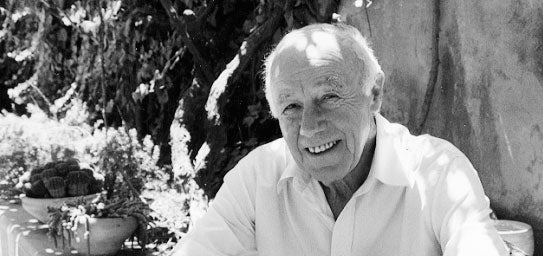

As he walks through his Jerusalem neighborhood overlooking the Old City, Simcha “Kazik” Rotem points out to a visitor that these houses were under fire during the 1967 Six-Day War. He used the Polish Gentile name Kazik in the Warsaw ghetto in 1943 as part of a disguise. There is no fear in Kazik’s voice as he speaks of the war in Jerusalem. But then, why would a man who survived the hell of the Warsaw ghetto ever again feel fear?

Kazik is one of the few surviving Warsaw ghetto fighters. How did he survive when so many others did not? To his anguish, it was a question many asked when he arrived in British-occupied Palestine in 1946. To avoid the questions—and the memories—he learned not to speak about his past.

Now, late in his life, Kazik has spoken. As he said in his 1997 Wallenberg Lecture in Ann Arbor, “The thought of fighting in the ghetto was totally unrealistic and contrary to everything the word ‘ghetto’ represents.” But Kazik and his brave colleagues did decide to fight, even though fighting the Germans meant almost certain death. After the German invasion of Poland, Jews in and around Warsaw were gathered up and forced to live in an area that made up only about 3 percent of the city. There were more than 500,000 people living in squalor in the Warsaw ghetto. The first massive deportation began in 1942. Spies from the ghetto told young resistance fighters like Kazik that the trains traveling from the ghetto to the camps were leaving the camps empty. Kazik and other Zionist youth group members decided to revolt.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising began in April 1943. With mines, grenades, pistols and Molotov cocktails, Kazik and the other Jewish fighters killed a number of Germans who came to attack the stronghold within the ghetto. Then the Germans attacked from outside the ghetto, burning down all the shelters and equipment the fighters had left. Kazik and some other surviving fighters tunneled outside the ghetto walls. However, that was not the end. “Unfortunately, we had no one to rely on except ourselves,” Kazik recounts in his book, Memoirs of a Warsaw Ghetto Fighter. “In my innocence I had thought that by getting out of the ghetto I had accomplished the essence of my mission…but we were still at the very beginning.”

He was at the beginning because of incredible selflessness. Kazik could have chosen to save himself, but he and the others who escaped decided to return to the ghetto through the sewers to save the remaining fighters. Crawling through the stench, Kazik reached the ghetto but found only ruins. “My life passed before my eyes, like a film, at a frantic pace,” he continued. “I saw myself fall in battle as the last Jew in the Warsaw ghetto. I had begun to lose all thoughts of survival. With a sudden effort, I wrenched myself free of thoughts of suicide and decided to return to the sewers.” There, Kazik encountered more Jewish fighters who had escaped. Although some of the fighters survived, the Nazis had killed most of them as they emerged from hiding.

The handful of remaining ghetto fighters was not yet safe. Still disguised as a Polish Gentile, and always wary of traitors and informers, Kazik continued to live in and around Warsaw, even escaping, through wit and luck, several detentions by the Gestapo. After Warsaw was liberated in January 1945, he learned of a miracle—his parents were still alive. Although his brother and one of his sisters had been killed, the family was among the few to emerge with even remnants intact. Kazik finally realized his boyhood dream of living in Israel by joining the clandestine Aliyah Bet immigration in 1946.

Kazik’s heroic deeds are shadowed by tormenting memories of the ghetto. He told a rapt Ann Arbor audience, “One night I was on patrol in the nearly completely destroyed ghetto. I came upon a heap of human bodies. There was a sound of crying, and there was a dead mother still holding her baby. I stopped for a moment, then went on. The Germans had succeeded not only in annihilating the Jews, they had also robbed me of my humanity.”